Read this story in Nepali: अलपत्र राष्ट्रिय बीउबिजन कम्पनी, जताततै ‘हाइब्रिड’, खै रैथाने बीउ !

Thirty years ago, seeds produced in Ghorahi were not just consumed in Nepal, but were also exported. Nepal produced vegetable seeds and exported them to India, Bangladesh and other countries. Radish seeds produced in Ghorahi were exported to Bangladesh, according to government data. The demand from Bangladesh was high as Nepali seeds were considered higher in quality. Besides radish, seeds of cauliflower, eggplant, tomato and other vegetables were exported to Bangladesh and other countries.

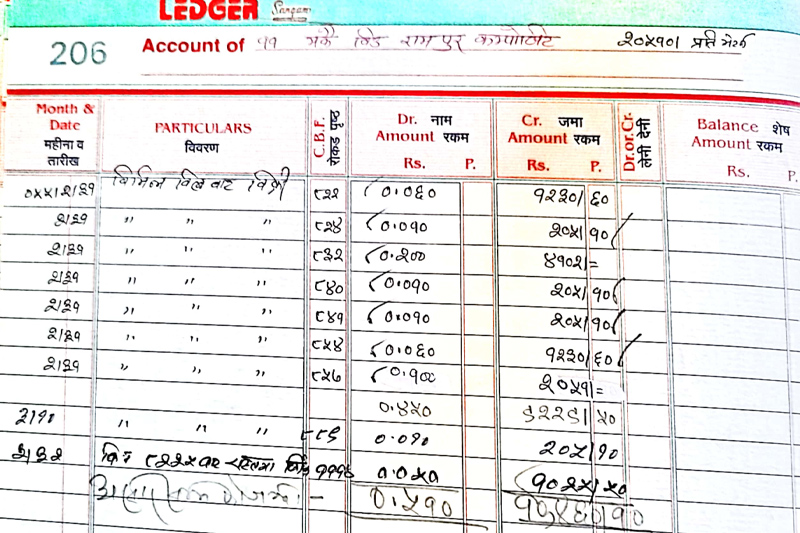

In fiscal year 1997/98, 5286.550 tons of radish seeds were sold from Dang, according to the records maintained by Krishi Samagri Company. Out of this total, 11 tons were exported to Pyuthan district, 5 tons to Chaurjahari, 20 tons to Rolpa, 520 tons to Dhankuta and 4600.550 tons to Kathmandu.

In fiscal year 1997/98, 5286.550 tons of radish seeds were sold from Dang, according to the records maintained by Krishi Samagri Company. Out of this total, 11 tons were exported to Pyuthan district, 5 tons to Chaurjahari, 20 tons to Rolpa, 520 tons to Dhankuta and 4600.550 tons to Kathmandu.

Sixty-five-year-old Madan Sedai, a resident of Ghorahi Sub-metropolitan City, was a former employee of Krishi Samagri Company. Around 1992, radish seeds from Dang were sold to Bangladesh, Sedai recalls. “We would buy the seeds grown by farmers, send them for certification at the Khajura Test Center, and then sell the seeds,” he says. “In 1992, we sent 50 tons of radish seeds. When I was still an employee of Krishi Samagri Company (then corporation), I remember exporting radish seeds to Bangladesh for three years.”

Rice, wheat, and vegetable seeds that were processed in Ghorahi would be transported to various districts from the east to the west. Sedai says that the seeds were sent to Jhapa, Janakpur, Sarlahi, Mahendranagar and Kanchanpur. “As production had not yet started in other places we distributed the seeds from here in 1992,” he says, “Seeds were sold in every nook and corner of Rapti zone from Ghorahi itself.”

According to the company's records, seeds exported from Ghorahi included not only vegetables but also rice and wheat. In the fiscal year 1997/98, 1,200 tons of mustard green seeds were exported. Of these, 2.5 tons went to Pyuthan, 3 tons to Charjahari, 5 tons to Rolpa, 20 tons to Dhangadhi, and 1,165 tons to Kathmandu. In the same year, 2,000 tons of onion seeds were exported. Of these, 40 tons went to Pyuthan, 3 tons to Charjahari, 20 tons to Rolpa, 50 tons to Bhairahawa, 205 tons to Nepalgunj, and 1,718 tons to Kathmandu.

The office records indicate that 13 tons of string bean seeds were exported in the fiscal year 1997/98. Toparam Gautam, the chief officer at Ghorahi for Krishi Samagri Company, states that at that time, seeds were sent to Pyuthan, Rolpa, Lamahi and Tulsipur, among other locations. The company's records show that 2 tons of string bean seeds were sent to Pyuthan, 3 tons to Rolpa, 4 tons to Charjahari, 1 ton to Lamahi, and 2 tons to Tulsipur. Additionally, 5 tons of yard long bean seeds were sent to the Tulsipur office.

Seed storage space now used for storing fertilizer

Three decades ago, Ghorahi used to export seeds to Bangladesh, but is now reliant on hybrid seeds imported from Bangladesh. The hybrid seeds, considered to be of higher quality, dominate the market. However, these seeds are a headache for the farmers in Ghorahi.

In 1997/98, the World Bank recommended creating separate entities for seeds and fertilizers to promote agricultural development in Nepal. On May 8, 2002, Krishi Samagri Sansthan was divided into two separate entities: the Krishi Samagri Company and the National Seed Company. This decision was likely influenced by the World Bank report.

Both companies subsequently ceased receiving grants. Starting the following year, foreign hybrid seeds entered the Nepali market.

The seed processing equipment in Ghorahi remains idle. Despite the equipment's substantial value, the government has shown little interest in its maintenance or use.

Provided as grants to Nepal with German technology, these seed processing machines have parts that are not readily available in the country. Due to a lack of repair parts, these machines are locked away, imposing hidden costs on poor farmers. They are forced to purchase expensive imported seeds from abroad.

In the past, the seed processing unit employed 15 staff members, including agriculture officers and lab technicians. The facility was well-managed physically. The Krishi Company Limited office building was originally used for seed processing. On the south side of the building, there was a dedicated area for processing and storing rice and wheat seeds. Currently, this space is occupied by old, broken machinery. The seed storage area is now being used to store chemical fertilizers.

Farmers forced to buy expensive seed

Kashiraj Nepal has been operating Nepal Agrovet in Damodhar Chowk, Ghorahi, for the past 34 years. He sells seeds purchased from the Krishi Samagri Company. The company used to buy seeds from farmers in Rolpa, Salyan and Dang, grading them before selling them to retailers like Nepal Agrovet. Nepal Agrovet also purchases tools, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides from Krishi Samagri Sansthan to sell to farmers.

"In the past, you could buy a gram of mustard green, radish or garden cress for 25 paisa," Nepal recalls. "Only certified seeds were sold, ensuring high yields."

He is concerned that foreign hybrid seeds, which now dominate the market, have pushed native seeds toward extinction. Due to a lack of conservation efforts, many Nepali seed varieties have begun to disappear from villages.

“There are no native seeds left," Nepal claims. "Genetically altered seeds have led to the disappearance of local varieties." He adds that in the past, local seeds were conserved. "If planted local seeds produced fruit, those seeds were used again," he explains. "Now, with genetically altered seeds, farmers are forced to buy new seeds every year. This not only burdens the country with import costs but also forces farmers into a perpetual cycle of seed purchases."

The annual necessity of buying seeds has made farming increasingly expensive. "This is a lamentable situation for Nepal," he states. "Our national capacity for seed production and export is extremely weak."

Nepal imports seeds from various countries, including India, Japan, China, Italy, Chile, the USA, New Zealand, Thailand, the Netherlands, Australia, France, Taiwan, Lebanon, Switzerland, Indonesia, Korea, and others. However, farmers in Ghorahi aspire to be self-reliant in seed production. Instead of importing hybrid seeds, they desire to use and promote local varieties.

Neither budget nor grant for seed

On May 8, 2002, Krishi Samagri Sansthan was divided into the Krishi Samagri Company and the National Seed Company. The Krishi Samagri Company was assigned responsibilities related to fertilizers, while the National Seed Company focused on seed-related work.

Farmer Bhim Bahadur Chaudhary of Ward No. 6, Ghorahi Sub-metropolitan City, attributes the division and weakening of Krishi Samagri Sansthan to government policy. He states that since the division, programs benefiting farmers have declined. "The government itself could not tolerate the government relief to farmers and the grants in the agricultural sector," he says. "After that, the company began to collapse, and programs that benefited farmers started to decline."

Until 1992, there were government grants available for farming tools. However, these grants for fertilizers and seeds were removed in 2002. There was a legal provision for tax deductions on fertilizer imports and VAT levied on private businesses. Instead of importing fertilizers, businesses fabricated import documents to claim the VAT amount. This resulted in farmers not receiving fertilizers while business people profited.

The government was also frustrated by the lack of fertilizer imports. In 2009, then-Finance Minister Dr. Baburam Bhattarai initiated a grant of 50 crore rupees for fertilizers, which continues to this day. In 2018, the National Seed Company was merged with the Agriculture Equipment Company, forming the Krishi Samagri Company Limited.

Currently, seed processing in Ghorahi under the Krishi Samagri Company is closed. The equipment there is non-functional. There is no budget or grant allocated for seeds. The government is responsible for the disarray in the seed processing industry. While some seed processing work is being done through Krishi Samagri Company's regional offices, it has not been expanded to the district level. Seeds do not reach the section offices, forcing farmers to buy expensive seeds. The equipment in Ghorahi has not been upgraded since 1991, and the government has not paid attention to the purchase of modern machinery.

Toparam Gautam, the chief of Dang district for Krishi Samagri Company, stated that the Ghorahi facility is limited to buying and selling fertilizers. He emphasized that a seed company should not be confined to the trade of chemical fertilizers. "Native seeds produced by farmers were bought and sold through this office. If the government takes the initiative, we can do more," he says.

Dissolving a seed production facility is a wrong government decision, according to agricultural specialist Krishna Paudel. "They only bring fertilizers because of the associated commission," he says. "Farmers cannot afford to pay commissions for selling seeds. That's why the government stopped the seed trading center. The system is driven by cronyism, involving everyone."

Paudel, an advocate for "farming for food," is concerned about the disappearance of native seeds. "Farmers were taught that to increase productivity, they must use genetically altered seeds," he says. "This is a game of capital and commission. As a result, our native seeds are disappearing."

Farmers are in a difficult situation because they cannot sell the seeds they produce and are forced to buy expensive seeds. "Buying foreign seeds is profitable for businesses and allows them to earn commissions from imports. Seeds are controlled by multinational companies for their benefit," he says.

Due to the lack of attention from the state and concerned agencies, local seeds and their genes are being lost, Paudel warns. "To be honest, multinational companies have been selling our seeds back to us," he says. "We lost our native seeds in the name of the green revolution. Not only seeds but also local fertilizer and pesticide production methods have been lost. Using chemical fertilizers to increase productivity is unsustainable. We need to reinstate organic farming methods."

Nepal considers agriculture as the primary foundation of its economy. Paudel argues that Nepal cannot progress in agriculture by losing native seeds.

Seed got hijacked in a box

Dr. Krishna Paudel, Agriculture Specialist

Five essential elements are necessary for an agricultural system: fertilizer, irrigation, seeds, tools and land. For now, let's focus on seeds. […] (Something is missing) stated that agriculture would be modernized. (The agricultural sector can be modernized.) Hybrid seeds are a consequence of this modernization. Businesspeople saw a profit opportunity in this. "If you control the seeds, you can control tens of thousands of farmers," they reasoned, and entered the market. The government should have maintained control over seeds. Multinational companies now have a monopoly on the market. Hybrid seeds are not inherently bad, but they are neutered, meaning they cannot be used for a second generation. As seeds purchased this year cannot be used next year, farmers are forced to buy new seeds annually. This makes farming expensive as farmers must invest in seeds every year. Because of this annual investment, farmers will naturally seek high-yielding hybrid seeds, leading to the replacement of native seeds. This is not something a farmer can do alone. The state needs to be active in this area.

Currently, 97 percent of greens and vegetables and 90 percent of grain seeds are imported. We are completely dependent on others for seeds. The countries that export seeds to us send them after improving their yield capacity. We could do the same. We can improve the quality of our native seeds. To achieve this, the government needs to make maximum efforts and invest in research. Only then can we save agriculture and our native seeds.

Read Our Republishing Policy here.